Samurai

Apparently they are more commonly referred to as Bushi in Japan? We went to see the British Museum’s exhibition which explains the long history of the Samurai. Beginning as medieval warriors, they effectively became the Japanese upper class until their abolition in the late nineteenth century, when the rule of the Emperor was restored and the Shogunate brought to an end.

Like their aristocratic counterparts in Europe, the Samurai retained an affection for swords and suits of armour. One set of Samurai armour here was sent to King James (I and VI) who would surely have understood the double significance of the compliment and warning it embodied. Another suit was later sent to Queen Victoria. While they retained a sense of themselves as warriors, the Samurai developed an interest in drama and culture generally, which may have helped while away the days they were required to attend the court at Edo (rather the way Louis XIV made the French nobility come to Versailles?) As a whole social class they naturally included valiant women, and it seems gay and/or cross-dressing young men were not unknown.

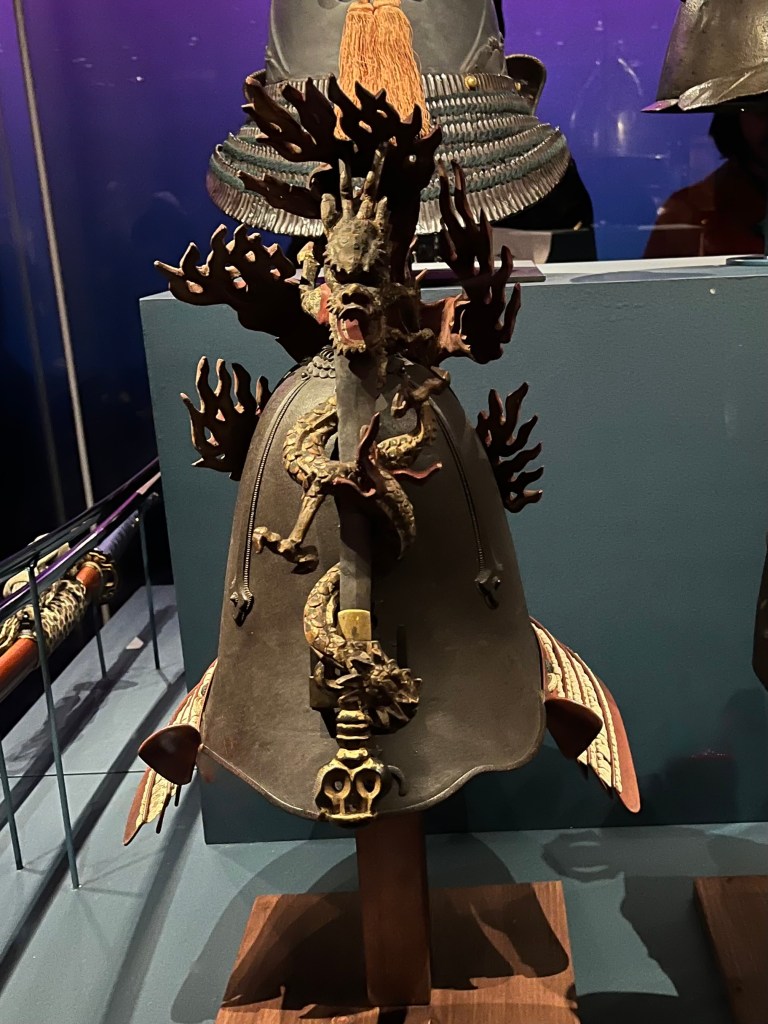

The exhibition features a wide range of fabulous and illuminating artefacts, but it is those extraordinary helmets that are really the stars. They are elaborately decorated with dragons, birds, and a finely worked butterfly, and there is one with leaves that Katharine said resembled a pixie hat. One Samurai seems to have been unable to decide between horns and a massive fist – so he got both. These all seem rather impractical: European knights had fancy tournament armour with decoration and crests, but when it came to an actual fight they were inclined to switch to the plain, streamlined steel that best deflected blades and points. It seems that in Japan being visible and showing high status was more important than guiding weapons away from your cranium. The followers of each Daimyo (top Samurai) had a different style of cover for the heads of their spears, and apparently there were actually spotter’s reference books, so you could identify which great lord was passing by on the weary trip to or from Edo.

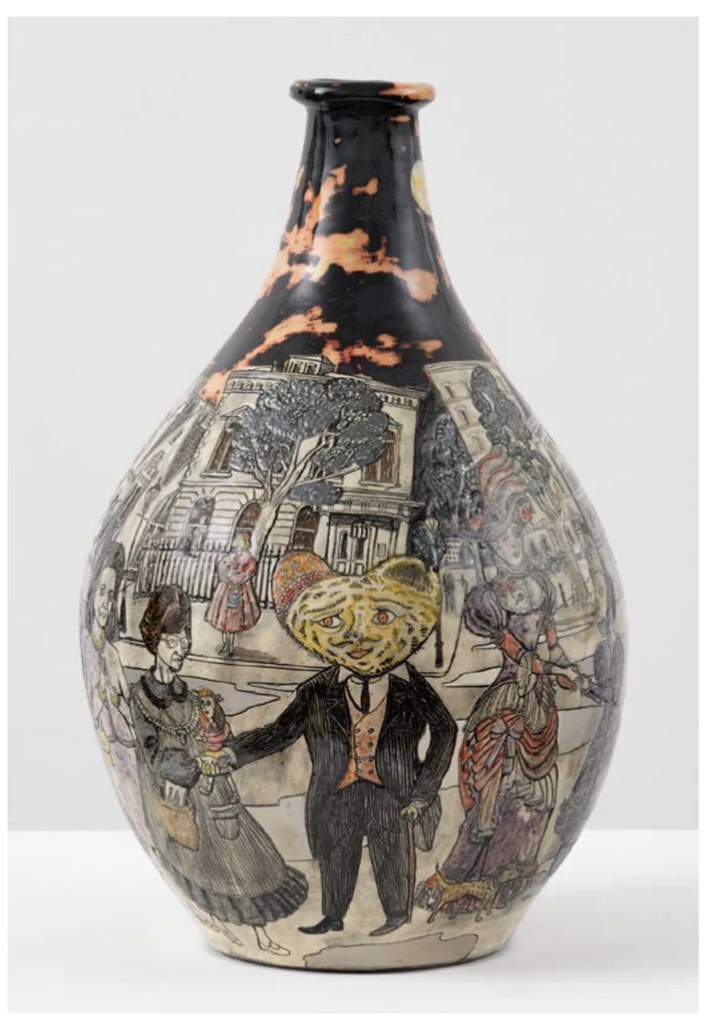

Very interesting. Here is King James wearing his Samurai armour (this never happened).