Susan O’Neal

My old writing chum has an elegant new blog – check it out.

Reviews of books. exhibitions, and other stuff I have seen.

My old writing chum has an elegant new blog – check it out.

We went to see Jesus Christ Superstar at the the New Theatre, Wimbledon. It’s still a great show some fifty years after it first turned musicals upside down. This is a lively production based on the Regent’s Park version, with a single set remaining in place throughout. There are nice touches – at the Last Supper the apostles strike the poses they have in the famous Leonardo fresco – but giving Christ a guitar (and baseball cap) doesn’t really work.

I’m always slightly surprised by how much many religious people like JCS, because it is a pretty agnostic account. No resurrection, no miracles, and Christ as doubting and kind of burnt-out. There are many references to his teachings, but they don’t get much of a showing. In fact when there’s an argument about principles it’s hard not to feel that Judas wins (‘people who are hungry, people who are starving, matter more than your feet and hair’). But I suppose the title warns us up front that this is about celebrity more than holiness.

It is certainly a great evening, and the audience loved it: some were just a bit too keen to start applauding when the show really required silence. But this is probably the outstanding example of a show where you don’t just leave humming the tunes: you’re doing it on the way in, too.

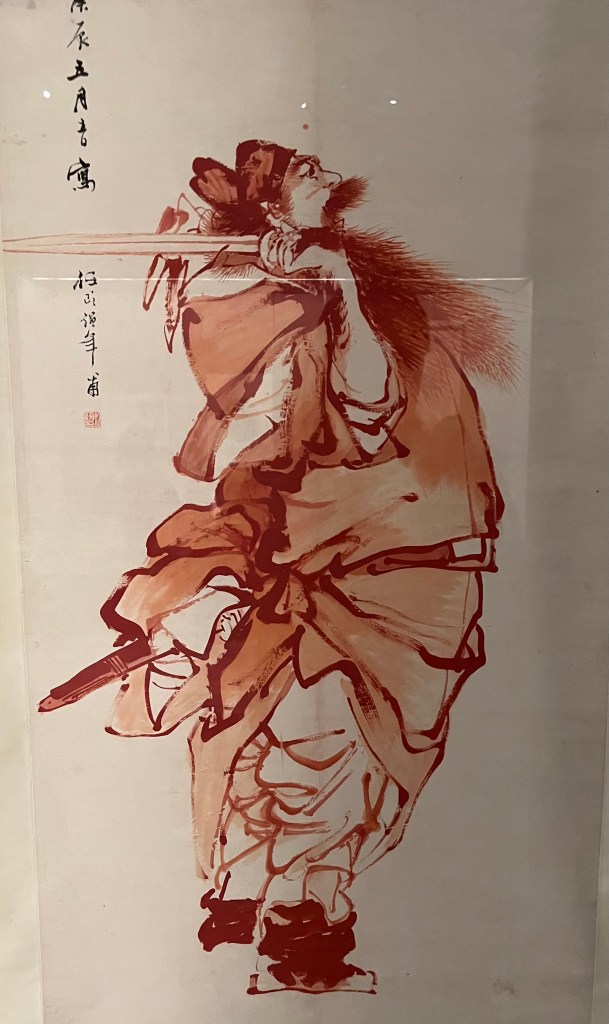

My daughter Elizabeth kindly organised a trip with her sister and me to see the theatrical production of Spirited Away. You probably know the film, Miyazaki’s most famous, which has become a much-loved classic here as well as in Japan. It’s about a girl navigating the dangers of a spirit bath-house, filled with strange but sometimes friendly creatures. Above you can see the Radish Spirit in the cartoon and in his theatrical version.

Being full of magic and weird beings, this is not a story that is straightforward to present on stage, but the designers have done a great job. They usually allow us to see how the tricks are done, but the effects are none the worse for that. The story is delivered pretty faithfully, following the film very closely, and it helps that probably everyone sitting in the Coliseum knows and loves the film.

This is, I think, the original Japanese cast, and the dialogue is in Japanese with the Coliseum deploying the surtitles it is famous for using with opera. It’s a deservedly popular show, and elsewhere in London you can already see a theatrical version of My Neighbour Totoro, another Miyazaki film. Someone must surely be thinking about doing Howl’s Moving Castle, though perhaps that one is a more complex business. Rather than the film being an original work, it is a significantly rewritten version of the story by Diana Wynne Jones, which has itself already been turned into a stage show…

We finally went to the British Museum’s highly-praised exhibition about life as a Roman soldier. It is illuminating, giving an insight into what was in many ways the heart and epitome of the Empire. Clearly on display here are some of the well-known features that made the Roman army so successful. It recruited anyone who met the height requirement without bothering about where they came from: it taught them basic Latin and sent them all over the place, turning them into loyal, well-off citizens who would settle and stabilise the provinces. There were only so many Greeks or Egyptians, but anyone could become Roman and enjoy the substantial opportunities that went with it.

The exhibition makes considerable use of soldier’s gravestones. One interesting thing about them is that they were often paid for by the dead soldier’s slaves, set free on his death. This reinforces the sense I picked up from the Pompeii exhibition, that Roman house slaves were often treated almost like family: better than the free servants at Downton Abbey.

The exhibition includes many unique and remarkable items, including the only surviving legionary’s shield and some extraordinary cavalry parade helmets which include masks, one of which was supposed to make the rider look like an Amazon. The suit fashioned from a crocodile’s body is probably more weird than representative, though you can see why the curator couldn’t resist it.

It’s a very child-friendly exhibition: so many large cartoons and features with Rattus the cartoon character you almost begin to wonder whether adults are welcome.

We went to see the National Gallery’s blockbuster exhibition of the work of Frans Hals, a good follow-up to our visit to his museum in Haarlem (and in fact we met a few old friends again).

Hals is notable for the lively characterisation of his portraits. A note in the exhibition rightly says that nobody painted nonchalance like Hals, but his people are also completely believable and full of energy.

He’s also known for the loose style he adopted, especially in his later years, when a few slashing diagonal strokes of the brush would skilfully suggest lace or fabric. It was this trait that endeared him to Van Gogh and other later painters. Look at how the details of this gent, convincing at a distance, are just rough and sketchy brushstrokes close up.

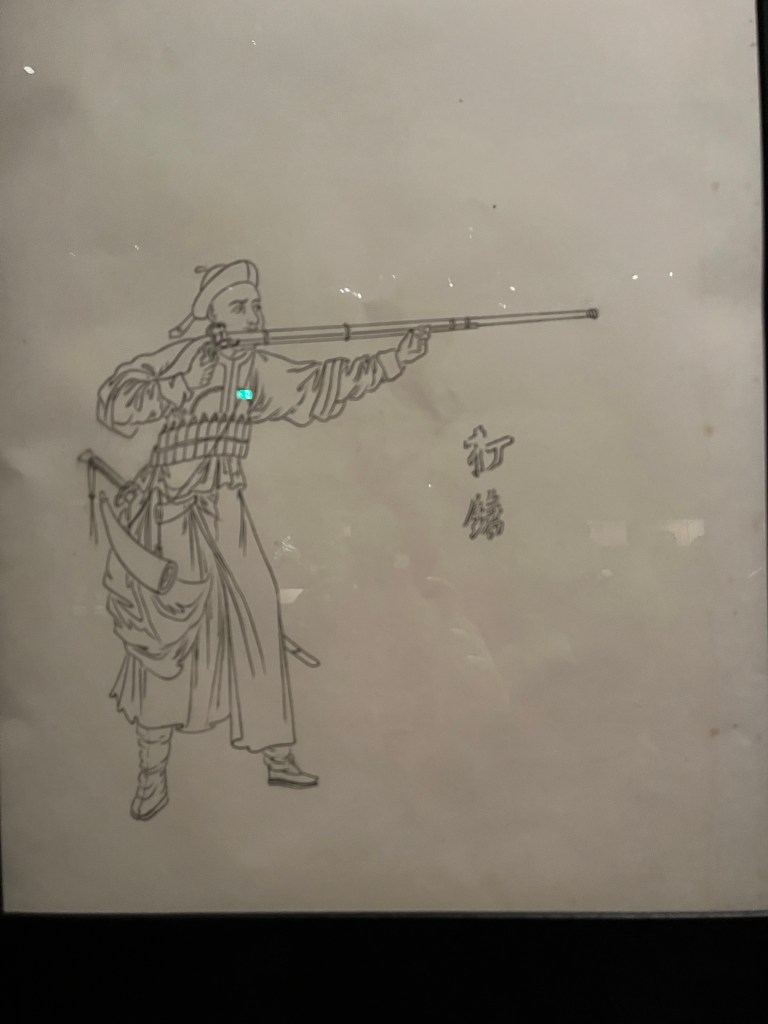

A belated hat-tip to the British Museum’s exhibition of artefacts from the last century of the Chinese Empire – here called the Hidden Century, but also known as the Century of Humiliation because of the way China was forced to accept the domination of people it had regarded as marginal barbarians.

This picture of Queen Victoria might symbolise the encroachment of the West, and of course we are reminded that many Chinese artefacts now in the West were frankly looted during the Boxer War or at other times.

If there’s a single message from the exhibition it might be that Chinese culture remained vibrant and productive, even benefiting from some Western influences. Here are some random items that caught my eye.

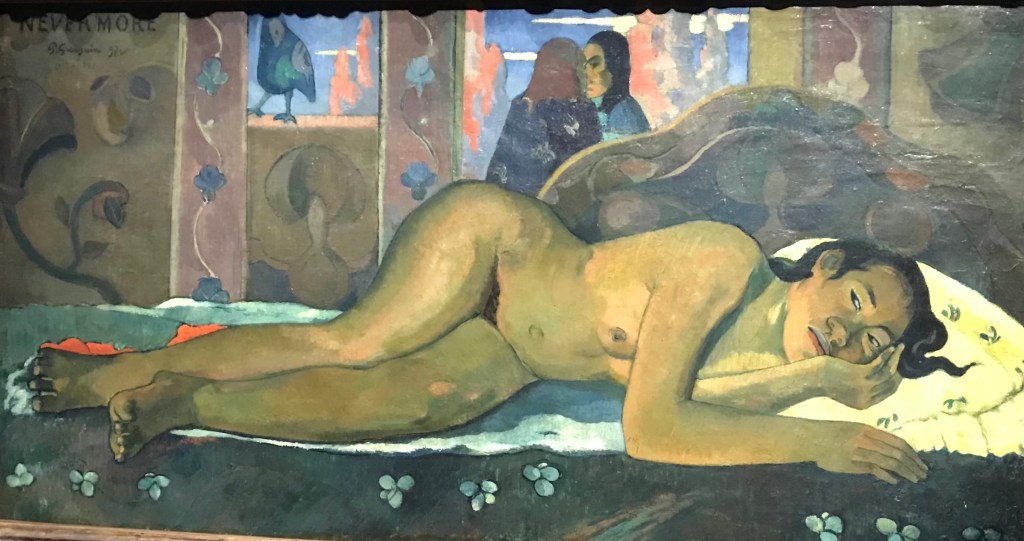

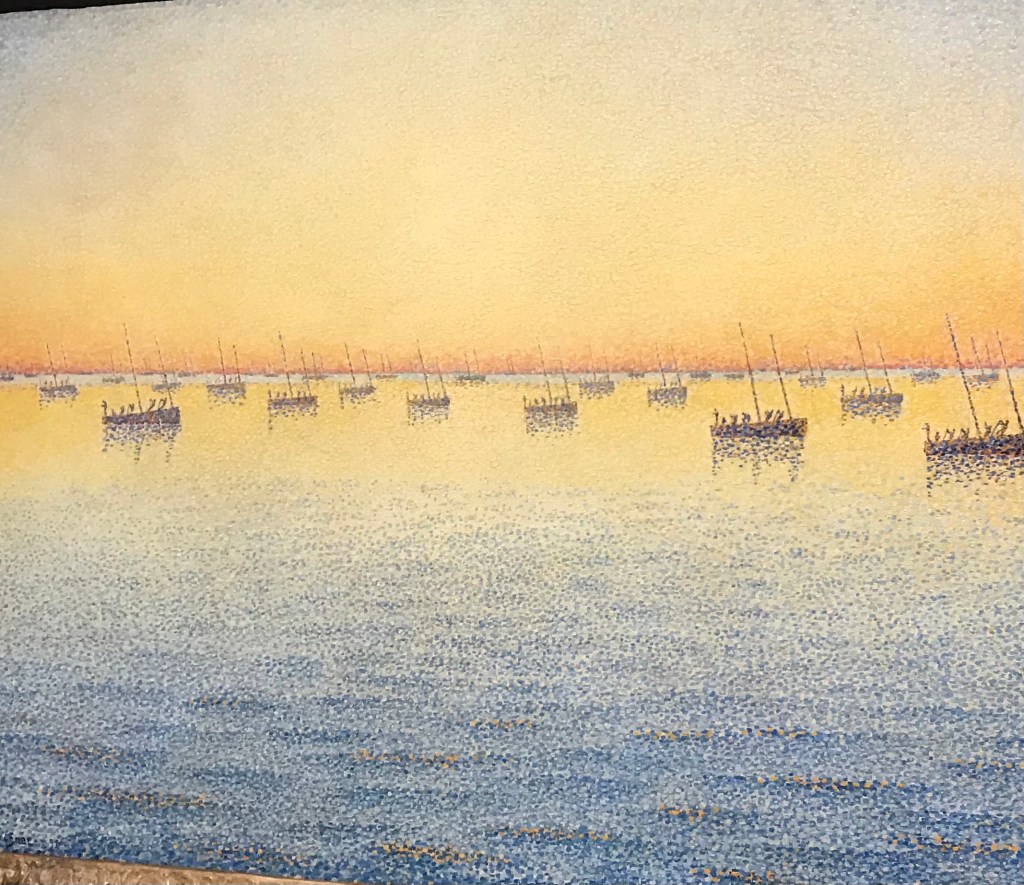

At the National Gallery, an exhibition that re-examines the innovative period that followed Impressionism, in both sculpture and painting. The focus is on the influence of three artists: Cezanne, Gauguin, and Van Gogh. Putting it simplistically there’s a suggestion that Cubism flowed from Cezanne’s work, Fauvism from Gauguin, and German Expressionism from Van Gogh.

Though it’s an enlightening framework, things are obviously more complex than that. To my untutored eye it all looks like a general explosion of originality, drawing on many influences as well as brand new thinking.

The exhibition, full of great stuff, is notably strong on pointillism, reminding us it isn’t just Seurat and Signac. I was also surprised yet again by more evidence of Picasso’s ability to produce brilliant work in every style, including of course, some that he helped invent.

This free exhibition features works by outstanding artists from many centuries, from a puzzlingly conservative Botticelli through Caravaggio, El Greco and Spencer to Zurbaran, taking in the Marvel comic Francis, Brother of the Universe. The notes gently mock the comic’s version of how St Francis received the stigmata through laser beams, but really it is no more dramatic than several paintings of the same crucial event, or Brother Leo’s actual first-hand account of a six-winged seraph.

The exhibition also features one of Francis’s own habits, presented in a golden frame. I suppose there is a suggestion that the habit can also be viewed as art, and indeed the exhibition offers a modern work using sacking. However, the habit also emphasises Francis’s historicity. Some of his feats (taming a wolf, walking through fire) resemble those attributed to older saints who are legendary bordering on mythical, but Francis is indisputably a real man. That raises the question of whether an exhibition organised around a theme tells us about the art or just about attitudes to the subject.

I suppose the message might ultimately be that artists use a theme to illuminate the concerns that mean most to them and their audience – Stanley Spencer using his own (strangely rotund) father to represent the saint. But whatever the rationale, it’s a great chance to see some fantastic paintings.

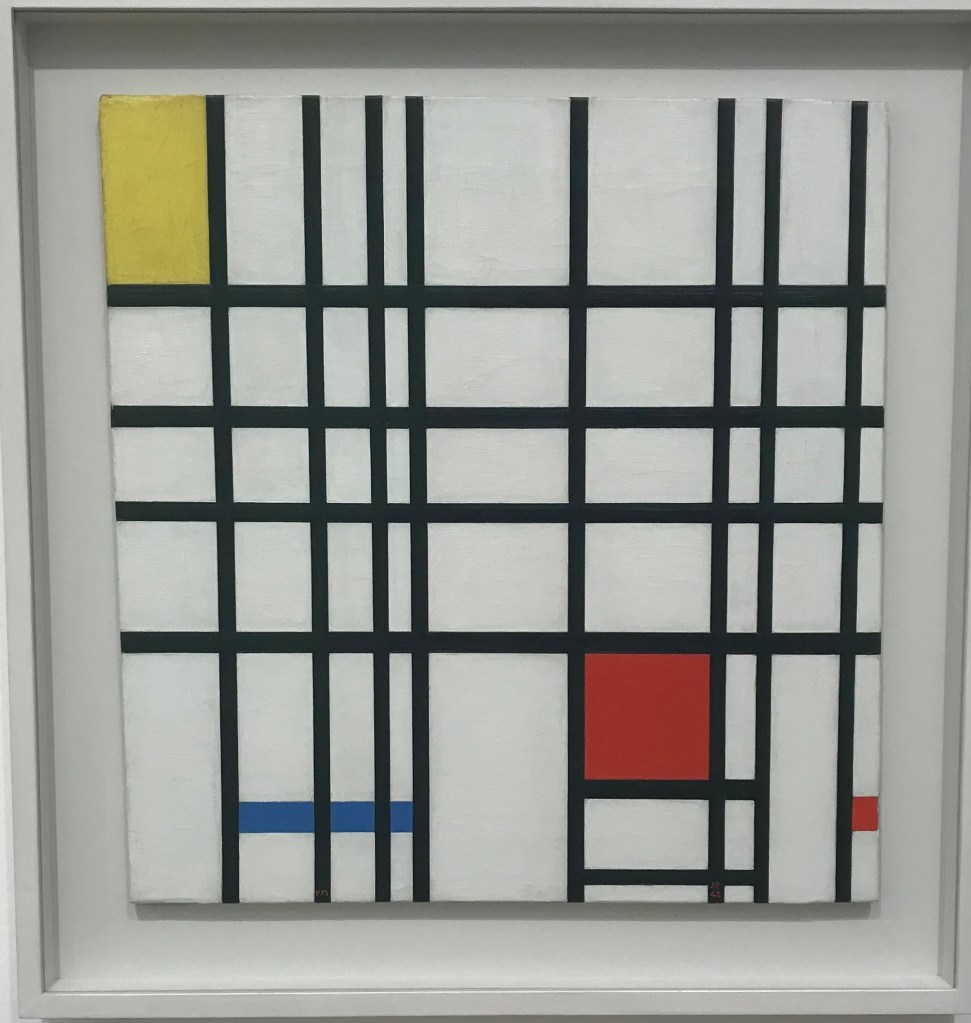

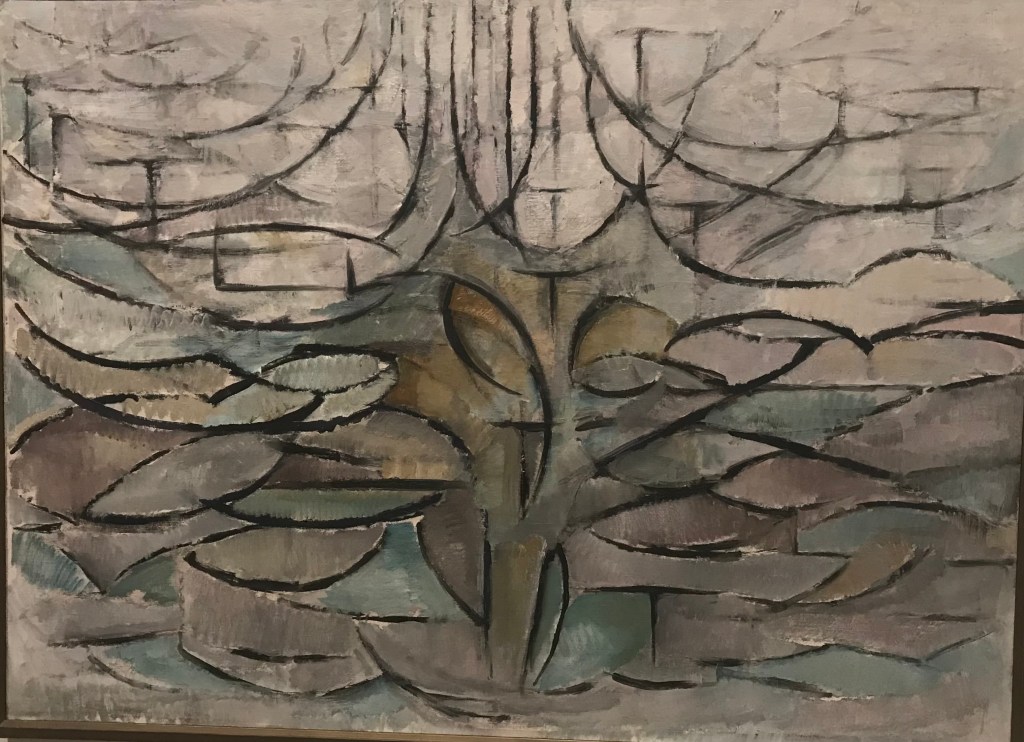

This exhibition, at Tate Modern, is a curious pairing. The Tate says both artists started from nature and developed a new abstract language: but they never met and did not influence each other, and their motives seem very different. They both used coloured squares sometimes, but that’s about it.

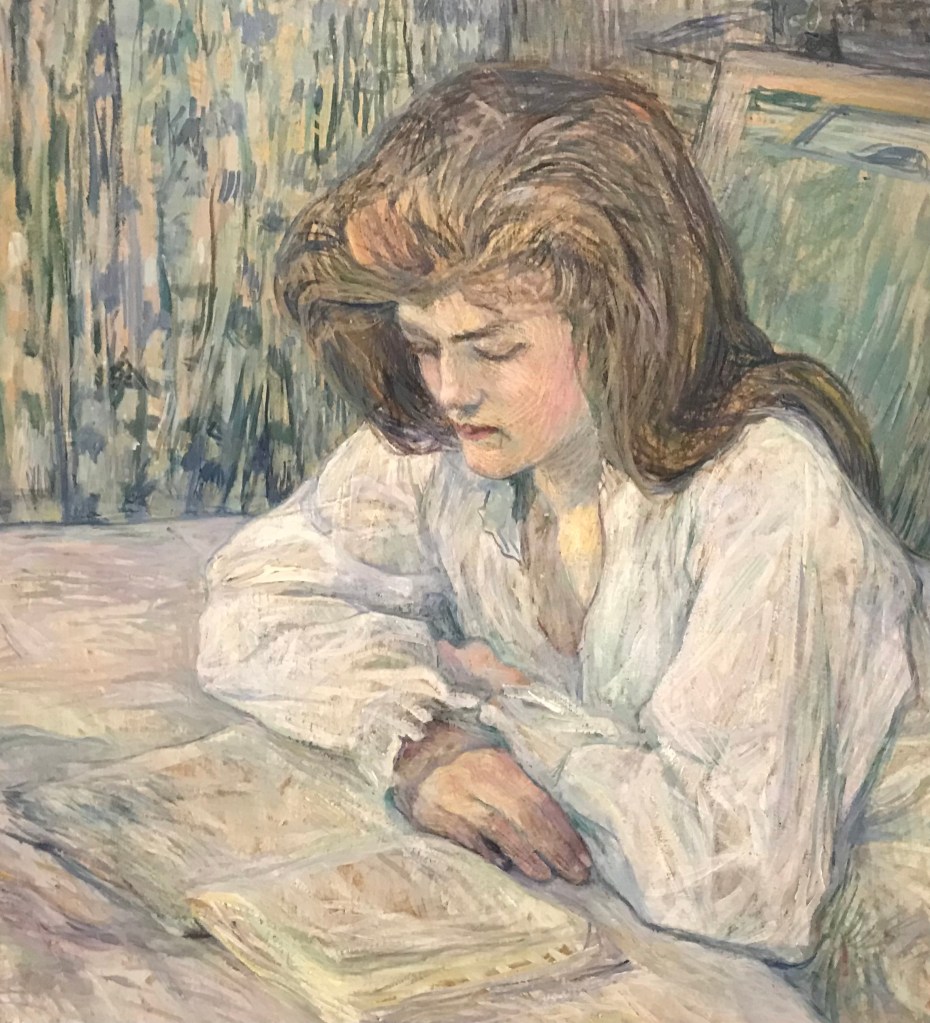

Mondrian painted flowers and landscapes in a conventional style as well as the rectilinear images with primary coloured blocks for which he is known. For me these push abstraction too far, but they are popular (Katharine likes them).

Klint is problematic in some respects. Most of her works were meant to illustrate her Spiritualist beliefs, and they are heavy with obscure meaning. She said that some were done with spirit guidance (which recalls some of Blake’s pictures, and there is a just a hint of his muscular symbolic figures in Klint’s stuff). She didn’t generally exhibit them, and it’s possible she wouldn’t have wanted them shown. I suppose the curators nevertheless see her as a significant gap in the story of art, but she seems well out of the mainstream. I must say that if her work had been shown in the sixties it might have found a following, and prints of her works might now be selling well alongside esoteric Tarot illustrations and mandalas in that kind of shop.