Down Street

We did the tour of Down Street, ably directed by a team from Hidden London under the aegis of the London Transport Museum. This is one of a number of abandoned tube stations, in this case on the Piccadilly line. Since opening in 1906, Down Street was never a great success. Down a side street and with better sited stations nearby it attracted few passengers and closed in 1932. In wartime, however, it got a new lease of life as a secret safe headquarters for the committee that ran the railways, and was used a few times by Churchill.

Conditions were not great, with corridors limited to the width of a standard tea trolley (obviously an essential). Yet people worked shifts, living in the station for weeks at a time without seeing daylight, putting up with limited bath and toilet facilities and rotating use of beds. The executive class were better looked after, with a kitchen that apparently served caviar and fine wines even at the height of the war. When peace came, it was pretty well abandoned, though it is still an official escape route from the Piccadilly line and the tube engineers make some use of it. There are plans to use its shafts to improve ventilation on the Piccadilly line, apparently.

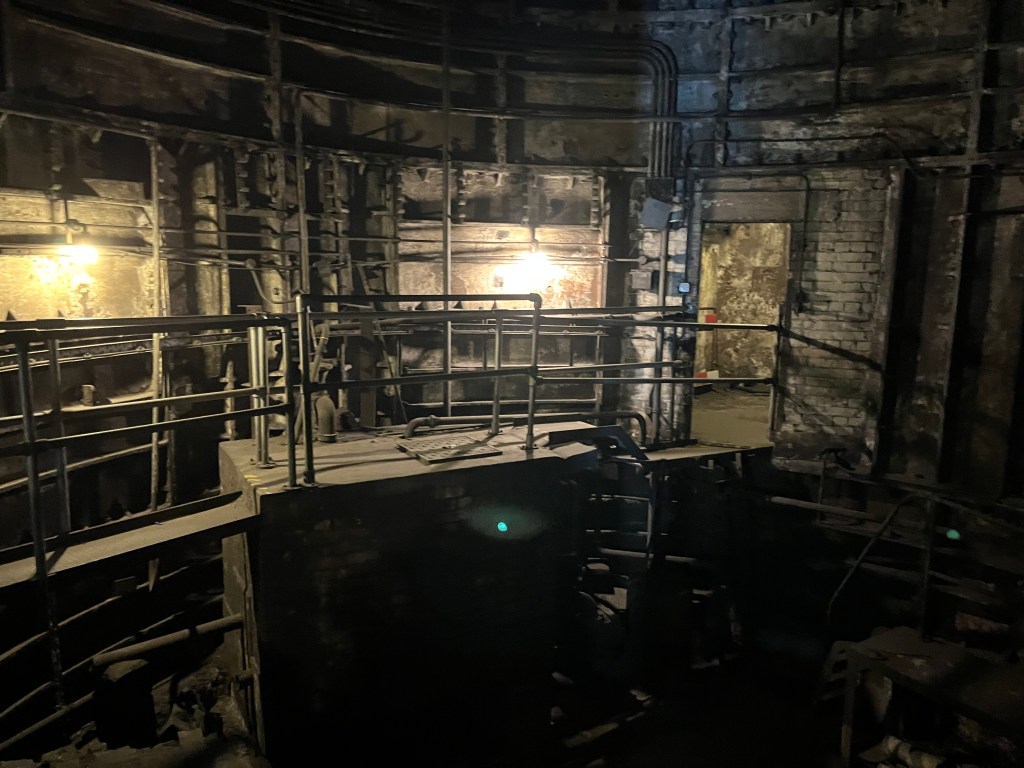

These days it is a bit of a wreck. The platforms were walled off in 1939, but the trains can still be heard, and seen flashing by in a few places. Odd bits of signage from different eras are still in place, and some of the fine old tiling. It seems odd to me that a space like this in the most expensive part of London is not more imaginatively used.