Hals at the NG

We went to see the National Gallery’s blockbuster exhibition of the work of Frans Hals, a good follow-up to our visit to his museum in Haarlem (and in fact we met a few old friends again).

Hals is notable for the lively characterisation of his portraits. A note in the exhibition rightly says that nobody painted nonchalance like Hals, but his people are also completely believable and full of energy.

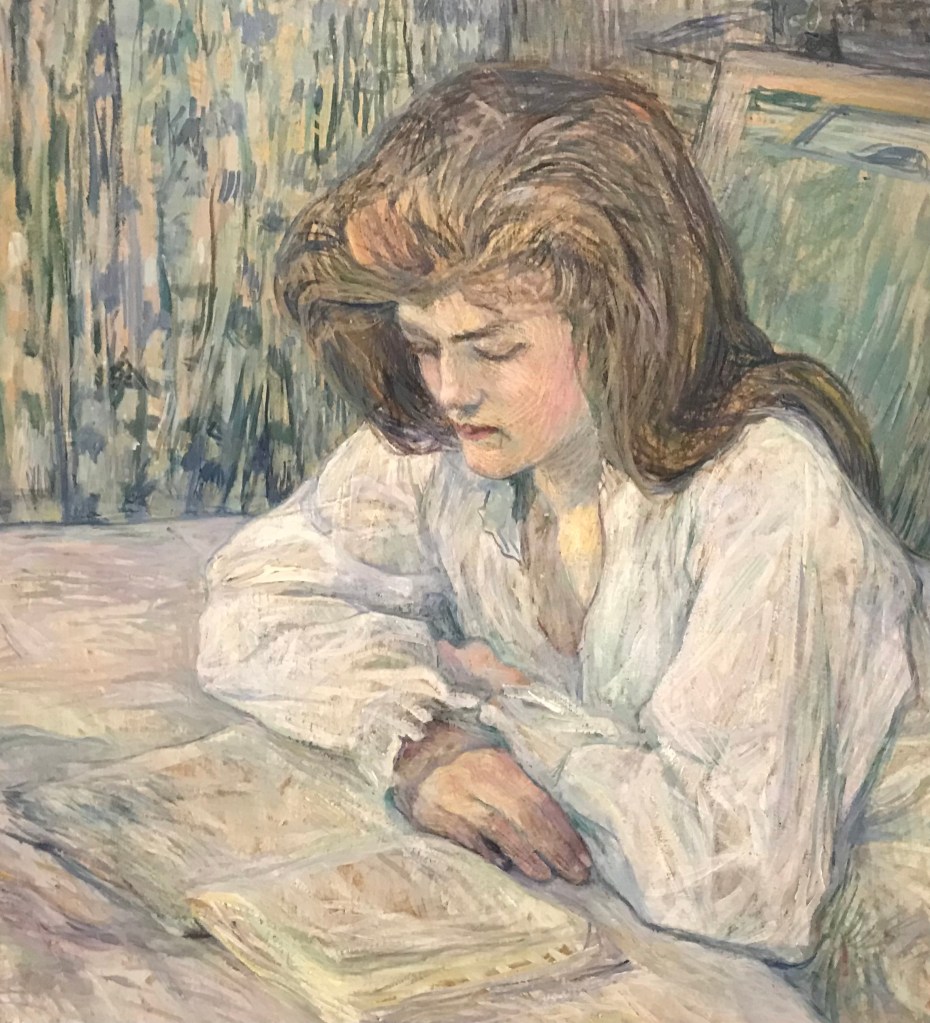

He’s also known for the loose style he adopted, especially in his later years, when a few slashing diagonal strokes of the brush would skilfully suggest lace or fabric. It was this trait that endeared him to Van Gogh and other later painters. Look at how the details of this gent, convincing at a distance, are just rough and sketchy brushstrokes close up.